In May, an organization representing cannabis farmers in Calaveras County, California—a rural enclave of 45,000 souls in the state’s historic gold country foothills—tried to buy the local police department an extra cop.

The farmers’ offer was not well received.

For the last three years, the public high school in Angels Camp, the county’s lone incorporated city, had been without a school resource officer. The school—Bret Harte Union High School, after the Gold Rush-era writer—once had a police officer on campus, but then the money had run out.

The county has been without an anchor employer industry since a cement plant closed in the early 1980s.

California’s boosters love to brag about “the world’s sixth-largest economy,” but such bounty is an abstraction in Calaveras, more than two hours’ drive east from San Francisco and about halfway between Lake Tahoe to the north and Yosemite National Park to the south. This year, county supervisors are grappling with a $3.6 million budget deficit, which has led to an understaffed jail. At the nadir of the Great Recession, unemployment soared to nearly 15% as nearly one in eight people lost their jobs. The jobless figure would have been higher were it not for the fact that half the people here are over 50 years old, and many are retirees, lured here in the 1990s by cheap land prices, golf courses, and senior-friendly housing developments.

The county has been without an anchor employer industry since a cement plant closed in the early 1980s. Aside from local government and a private hospital, the job market is almost entirely dependent on tourism. “It’s not that there are no decent employment opportunities here, it’s that they’re all taken,” said one longtime county resident and cannabis farmer. “You’re basically just waiting for someone to die.”

In 2015, the most recent year of California’s historic drought, a devastating wildfire swept through the region. More than 550 homes burned in the Butte Fire, a catastrophe that compelled some people to give up on life in the area, sell their land, and leave.

“Is this town not worth saving?”Jackie Heintz, retired Angels Camp city clerk.

The county’s name, Calaveras, is Spanish for “skulls,” a moniker granted, so the story goes, after an early European explorer found piles of human bones alongside a riverbank, later named the Rio de los Calaveras (literally, “river of skulls”). These days, with so many elderly residents and so few young people starting families, deaths are outpacing births by about 100 a year. And unlike other fast-growing California counties that have seen heavy a heavy migration of urban dwellers fleeing skyrocketing home prices, there aren’t enough newcomers moving to Calaveras to make up the difference. According to official state figures, the county has a negative growth rate.

To put it plainly: Skulls County is dying.

The city of Angels Camp itself, incorporated in 1912, is so poorly run, so corrupt, and there is so little interest among citizens in fixing it, that a grand jury recently suggested the city consider dissolution. That sparked a sorrowful plea in the Calaveras Enterprise, the local newspaper.

“Where are you men who graduated from Bret Harte and are now enjoying your life here in Angels Camp?” wrote a retired city clerk. “Is this town not worth saving?”

Many who grew up here have an interest in rejuvenating the region. But today, the only thing booming in Calaveras County is cannabis.

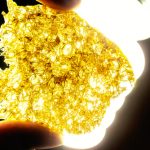

Weather in the foothills—hot days, cool nights, bone-dry almost nine months of the year—is ideal for growing the plant. Some horticulturists say it is the absolute best climate on the planet for cannabis.

Like most other rural areas of the state, marijuana has been grown here for decades with varying degrees of subterfuge. At least one major brand, Bloom Farms, has been based here for several years. Its CEO, Mike Ray, is a Calaveras County local, born and bred.

Following the devastation caused by the 2015 Butte Fire, when land was available on the cheap, growers shut out of the state’s Emerald Triangle “pot basket” flocked here. Ray, who weathered years of record-breaking drought only to lose his childhood home and entire 99-plant crop in the blaze, rebuilt and kept his business in the county. He now employs 50 people, with 10 working directly on the farm.

Some marijuana green-rushers bought land and set up sophisticated farms. Others, as the Sacramento Bee reported, merely parked old RVs on burned-out lots and started growing—in some cases, growing hundreds of plants on small, two-acre plots next to modest suburban homes.

According to the county planning department, there are now as many as 1,600 “commercial” cannabis farms in the county. By one estimate, a study conducted by academics from the University of the Pacific, in nearby Stockton, more than 2,600 people are now employed in the county’s cannabis trade.

If those figures are accurate, marijuana is easily the number one industry in Calaveras County. And even if they’re not, cannabis is already helping to balanced the county’s ailing books.

Last summer, officials confronted the obvious: Weed was the only thing going in Calaveras, so weed should be the centerpiece of the county’s recovery after the fire. Beginning last May, officials started handing out permits for some of the largest legal cannabis plantings in California: up to half an acre. (For context’s sake, a thousand plants—more than enough for a skilled grower, with help, to grow a literal ton in a season—can easily fit on one acre.)

More than 700 growers paid $5,000 apiece for the privilege.

In six months, marijuana brought in $3.7 million to Calaveras County. That’s in permit fees alone. Under a new cultivation tax—$2 per square foot of grow space for outdoor, $5 per square foot for indoor—the county is projected to rake in millions more this year and next. And if the county were to complement its wine and tourism trades with cannabis—with attractions like tours and tastings, like the ones big-thinking growers in Humboldt and Mendocino counties envision—it could mean even bigger things.

Calaveras could be the next Emerald Triangle.

“Calaveras really has the opportunity to be the Napa of cannabis,” Ray of Bloom Farms told me. “It’s two hours and fifteen minutes from downtown San Francisco. Humboldt has the volume and the title of the largest cultivator epicenter, but it’s six hours away. Nobody’s going to go up there. We could bring in tourism, hotels, restaurants.”

At the same time, marijuana has meant a mad rush of moneyed outsiders into what had been a sleepy, desiccated, and slowly crumbling community. This has caused a “panic” among locals, one grower told me.

“This was not what anyone wanted,” he said.

(1118)

Leave A Reply