THE FIRST TINGLE of THC hits him as he’s stretching his calves.

“I’m locked in,” he says, squishing two headphone buds into his ears. “This is going to be a great pace.”

The sun hasn’t yet risen over Colorado’s Front Range peaks, but Cliff D. (who asked not to be named), like many working-stiff triathletes, juggles a career—he’s a full-time strength and conditioning coach—with his own training and racing, and that means plenty of predawn workouts. But unlike the other guys circling Denver’s Washington Park in the early hours, Cliff has just eaten an energy bar that contains enough marijuana to numb a small elephant. To be precise, the homemade bar was packed with about 30 milligrams of the plant’s psychoactive chemical, tetrahydrocannabinol (THC). For a newbie pot smoker, the THC dose would be a knockout punch. For Cliff, that’s just breakfast.

Standing 5’6″, Cliff, 39, a hardcore athlete and former Division I soccer player who trains upward of 23 hours a week, has a thick chest and lean, muscular arms and legs. A lattice of tattoos peeks from below his sleeves, and his skin is tanned an even olive brown. He regularly completes Olympic-distance triathlons—which comprise a one-mile swim, 25-mile bike, and six-mile run—in a blazing two hours and five minutes. He’s won his age group at the South Beach Triathlon, and this year he finished third in his age group at the New York City Triathlon.

This morning, Cliff jogs off to run his warmup, which consists of two easy laps around the park’s two-mile loop. Then he completes four sets of one-mile fartlek intervals, which blend fast-paced speed work with recovery-paced jogging. The efforts are designed to ready his heart, lungs, and legs for the blistering 10K run that finishes off the triathlon.

His style is distinct and disciplined: He runs out over his feet with short, quick steps, emphasizing turnover instead of stride length. Each of his sets he completes with methodical precision; each foot strike is a mirror image of the previous one. By the time he’s finished, he’s drenched in sweat and panting, but grinning from ear to ear. “That was epic,” he says, as he extends a high five. His eyes are as big as soup bowls. “I found a guy who was running a 5:50 [per mile] pace and just sat on him. We were flying.”

Cliff is affable and even-tempered, and when you’re talking to him it’s easy to forget that his bloodstream contains a controversial chemical that’s fueled billion-dollar criminal empires, been the focus of Drug Enforcement Administration raids, and repeatedly commandeered national politics. But times appear to be changing.

Now legal as a recreational drug in Colorado and Washington State, and as a medical therapy in 21 other states, marijuana is slowly being seen as a socially accepted drug in the eyes of most Americans. According to a 2014 CNN poll, 55% of respondents believe it should be legal. Meanwhile, here in Denver, where pot shops now outnumber Starbucks, the drug’s former stigma is long dead and buried. Most Coloradans look upon pot as a weekend fun-enhancer, or a handy substitute for beer.

To Cliff, marijuana is something else entirely: It’s a genetically engineered workout supplement—a combined focusing agent for exercise and a pain reliever that numbs his post-workout aches. During a workout, he says, the THC allows him to stay focused on things like his heart rate, or stay motivated during a four-hour bike ride. “My mind is always all over the place, I can get caught up in what’s going on around me,” he says. “Weed helps me keep my mind focused, if you can imagine that.”

Chronic issues

Scientists have long known that THC, the core chemical compound in marijuana responsible for the plant’s mind-altering effects, works by concentrating on the receptors of the brain linked to memory, perception of time, and the pleasure of dopamine. In the case of pot, there’s plenty of scientific evidence out there to say that’s not a good thing—for exercise, or anything else.

This year, in fact, a team of medical researchers from Harvard and Northwestern universities published a landmark study in the Journal of Neuroscience, which concluded that marijuana use among young people impacted areas of the brain that regulate everything from emotion to motivation. The study, which focused on 40 young adult students, revealed that THC physically changed the density, shape, and volume of the amygdala and nucleus accumbens areas of the brain. In other words, the research concluded that marijuana may alter the physiology of the brain in potentially harmful ways.

That finding follows decades of public ire surrounding the use of marijuana, which has been roundly derided by doctors and parents alike as something extremely harmful to your health, if not a gateway drug to crack or heroin. Over the years, marijuana has been linked to everything from severe mental illnesses, such as schizophrenia and psychosis, to other problems such as depression, suicidal thoughts, and extreme paranoia.

And that’s to say nothing of just the simple state of being stoned. A study conducted in the 1980s by Richard Schwartz, M.D., of the Vienna Pediatric Associates, reported that in a survey of 150 marijuana-smoking students, 59% forgot what the conversation was about before it ended. According to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, “The more difficult and unpredictable the task, the more likely marijuana will impair [mental and motor] performance.” To echo the 1936 cult classic Reefer Madness, marijuana smoking is still a “drug menace which is destroying the youth of America in alarmingly increasing numbers.”

“Not all pot is created equal”

But Cliff doesn’t smoke pot. And the pot he uses isn’t “regular” pot. Instead, he prefers to eat his cannabis. Or, if he’s pressed for time, he’ll inhale marijuana water vapor from a handheld vaporizer he carries. “It doesn’t burn my lungs like smoke, he says.” He also rubs his fatigued muscles with a lotion that contains cannabidiol, commonly called CBD, a pot extract believed to carry a wide range of therapeutic qualities. Daily, he consumes marijuana in many forms and multiple times.

More important, the marijuana he uses isn’t your run-of-the mill weed, which he says leaves him “stuck on the couch” and “unable to get up.” His pot is essentially a boutique brand purchased at a medical marijuana dispensary. Cliff preaches a concept that’s become something of a cliché in the legalized marijuana culture: Not all pot is created equal. Gone are the days of smoking dry, crumbly leaves from your buddy’s backyard pot plant.

Today, countless marijuana growers genetically cross-pollinate purebred strains into hybrids and sell their pot as a high-end specialty product. Consequently, just as different grapes produce different wine flavors, sellers say, different marijuana strains produce vastly different psychoactive sensations. While one strain may leave you in a comatose state—a term known as “couchlock”—another may make you unable to stop talking. And professional pot reviewers discuss the buzzy sensations in various magazines, online forums, and blogs. As a result, today’s potheads are just as snobby as wine fanatics or craft -beer nerds. And Cliff is probably the biggest pot snob of them all.

After several years of trial and error, he’s found his daily medicine: a marijuana strain he says provides energy and focus, contains CBD, and doesn’t cloud his mind—a sativa-dominant strain called Super Lemon Haze. The Denver-based creator of Super Lemon Haze, Charles Blackton, known in the cannabis world as “The Lemon Man” for his potent strains of lemon-flavored marijuana, says this variety’s genetics come from sativa plants, believed to boost energy and alertness.

But, like most growers, Blackton also cautions that the body’s reaction to the drug varies from individual to individual. “I’ve heard a lot of similar stories: It gives them focus, it gives them mental clarity, they see pain relief,” Blackton says. “But your own body chemistry plays a role in what it does.”

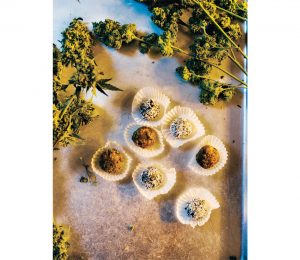

Whatever the case, when Cliff’s brain echoes with Super Lemon Haze, which he makes into raw vegan fruit-and-nut bars, he says, the distractions simply melt away into the background. When cycling, he feels an amplification of his calf muscles engaging as his foot swings to the top of each pedal stroke, just before his quads and hamstrings push down on the pedal. On a run, he sinks into the beat of whatever he’s listening to—usually a mix of Lady Gaga, Linkin Park, or various house music—then adjusts his pace to the rhythm.

“It slows my thought process down so I can evaluate thigns as they come to me, one at a time,” he claims. “It gives me a beat in my head that I can follow when I run.” While swimming, he visualizes his hand enterting the water at a 45-degree angle, catching the liquid, then pullling back to his hip before exiting the water again in one long, fluid motion. “I understand people who don’t want to race high because of the swim,” he says. “But to be honest, there’s nothing better than swimming as high as a kite.”

Cliff argues that his Super Lemon Haze is perfect for endurance exercise, pointing out that athletes frequently rush through their workouts or pay too much attention to the pace clock or their training partners. Swimming, cycling, and running, he says, are sports that revolve around repetitive motion, and thus reward extreme focus and an impeccable, machinelike technique. Taking Super Lemon Haze, he says, dials in his brain.

Cliff’s not alone. A slew of marketers are even promoting various strains of engineered pot as an essential part of an “active lifestyle.” Popular brand Dixie Elixirs & Edibles debuted ads this year featuring kayakers, skiers, and yogis with the tagline: “What kind of Dixie are you?” In San Francisco, ski promoter Jim McAlpine launched his 420 Games—composed of running, cycling, and, yes, Frisbee—to promote healthy marijuana use while exercising.

“Some people drink a few glasses of wine a night, but if you smoke weed, you’re a lazy stoner,” McAlpine says. “There’s no better way than an athletic endeavor to show that we’re not all couch potatoes.”

Yet despite the growing enthusiasm of progressive Colorado-based growers and marketers, and a wave of anecdotal evidence from countless pot users, virtually no research has been done to showthat new, strain-specific marijuana is healthier or “fitter” than other, more mundane varieties of weed. According to Suzanne Sisley, M.D., a former professor of the University of Arizona with extensive experience working with marijuana, we’ll never know the truth about marijuana until scientists also realize that not all pot is created equal.

“Research that looks at different marijuana strains needs to be done,” she says, “because these could actually be mental performance enhancers for the general population. Strain science right now is based solely on urban legends and what patients tell us.”

Vaping up while shaping up

As we pull up to Cliff’s Denver gym, in a former garage attached to a skateboard shop, several clients are already warming up for early-morning workouts. Cliff positions the men at various stations around the gym. While ’90s rock blares, the men undergo eight active isolated stretching (AIS) maneuvers before moving on to the main set.

At one station, one of Cliff’s clients, a lawyer, pushes a metal sled back and forth across the floor. At another station, a wealth consultant tosses a heavy medicine ball up against the wall, while next to him another lawyer uses a rowing machine. The workouts are part of Cliff’s self-titled Functional Intense Training System (FITS), which blends resistance training with high-tempo cardio. “These guys want to be fit and look good, but it’s not like they’re not drinking beer or having a good life,” he says. “I want all my clients to be able to hop in a 10K race, do a sprint triathlon, ski the best powder, or hike up Mount Kilimanjaro.”

The sales pitch is hardly unique within the workout world, but the message resonates with Cliff’s clients. He’s had to cap his client list at 16. As the men finish their workouts, the next client, a founder of one of Denver’s largest marketing and design firms and an innovator in the online music world, pulls up in a black SUV.

New clients are attracted by Cliff’s emphasis on technique, and remain with him because of his energetic personality, says one of his long-standing devotees. “There’s this vitality that oozes out of Cliff,” he says. “He’ll tell you all about his life. There aren’t too many things he won’t talk with you about.”

Marijuana is one of those topics. Cliff says he discloses his own personal marijuana use before working with a new client. After that, he gauges each person’s comfort level with it. If a client is extremely amenable, he may take a vape hit in their presence. If not, he’ll leave the pot talk at home.

Cliff’s final client of the day, a food scientist at a regional chain of organic bakeries, walks in around noon nursing some muscle soreness in his shoulder. Cliff produces a slim black stick from a plastic case. He presses the stick to his mouth, inhales, and blows out a cloud of water vapor. His client also takes a hit off of the vape pen and begins stretching his legs.

“If I’m sober and I hit the pain zone during a workout, I’ll probably bail out,” the client says. “If I’m a little high, I push through.”

As the two men continue their workout, the ’90s playlist advances to one final song. The voice of Sublime’s deceased frontman Bradley Nowell wafts across the gym.

I smoke two joints in the morning

I smoke two joints at night

I smoke two joints in the afternoon

It makes me feel all right.

Without hesitation, Cliff swivels around in a chair and points up. “I love this fucking song!” he says.

(1159)

Leave A Reply